I’m going to focus more than a few posts on here on reviewing and reflecting on sections of books I’m reading. For example, some reflections on chapters on immigration in the tome of New York City History, Gotham: A History of New York to 1898 and on a few chapters from Luigi Barzini’s The Italians: A Full-Fledged Portrait Featuring Their Manners and Morals from 1964. Those will come first.

I might also write some bits reflecting on Leo Pinsker’s essay Self-Emancipation, translated to English, which is about the Jewish “Dispersion” and nation in the nineteenth century. And after that, I might time-travel backwards through nineteenth century writers writing about Jewish dispersion and nationhood because, well, they seem refreshingly interesting at this point.

I’ve invested in ideas about cultures, nations, and imagination for a while, and been teaching migrants and migrating myself for a long while, and these are the books and PDF files around me at the moment.

There’s a lot of books on my to-read list. So, expect my thoughts on them in your inbox in the next few weeks if you subscribe. If you don’t, that is what will be going on here.

Before getting into the bits of modern European and Mediterranean history and its crossover into the Americas—specifically northeast Atlantic coastal U.S.—here’s a short bit about me. I’ve lived in many places over the past 25 years and currently am back in New York City, really not far from where I was born and raised in southeastern Pennsylvania at the edge of the suburban counties and the agrarian Germanic (Pennsylvania Dutch) counties, not far geographically at all but in every possible way, globally speaking—two totally different worlds and planes of existence.

Most people mistake me for Italian over anything else. Or if not Italian, something Mediterranean. A Turkish barber the other week asked if I was Moroccan. I couldn’t tell if he was joking or intentionally wrongly guessing but that was a new one. When I lived in Izmir for three months, people often approached me and asked questions like “is this the train going so-and-so direction?” or “which way is such-and-such?” in Turkish. I assumed that even while I didn’t look specifically Turkish, I appeared ambiguously enough that at six feet and with confident posture I seemed like a safe person to ask who might know some things. Older Turks seem generally more freely sociable than Americans, too. In Spain, people assumed I spoke Spanish more fluently a lot (I blended in as someone who’d understand more than the level I did). I got a coffee from a man in a food truck the other day and he asked where I was from. I said I was American and he probed, “no, really from,” and I said “Spain” (true if you go back far enough) then this man, likely Egyptian, proceeded to speak to me in basic Spanish. This is my new favorite method for practicing Spanish, and I will try it more. When I lived in Korea some Koreans guessed I was from Lebanon or Egypt. I don’t know why those places, but those predictions stood out. A month or so ago some young Orthodox Jews asked me if I was Jewish and I wasn’t in a talking mood, so I said no but I’m curious how the conversation would’ve gone if I’d played along. I’ve been profiled as almost every kind of Mediterranean except for French or Albanian or any of the Balkan coastal countries, though I bet I could pass for some sort of any of them as long as I didn’t try to say anything.

How people profile me reflects how they want to see me and what’s on their minds. But it’s interesting to be me in these situations because it gives me a little window to see them in return. I can be many things. The more I play with being in some grey area the more I get to react in a variety of ways. It seems like Sasha Baren Cohen recognized this sort of blank-slate identity-rôle-play and decided to master the art and create his own brand and style of comedy from it.

My lineage goes back to Europe eventually but more proximally my genetic roots are Puerto Rican and Pennsylvania Dutch/German; on these shores from the nineteenth century waves of Germans that landed probably in New York first then made their way to New Jersey and Pennsylvania. I grew up first steeped in the latter culture before moving closer to the more cosmopolitan suburbs of Philadelphia. The closest grocery store in my first home near French Creek State Park was populated with Mennonite food sellers where the Amish sold fabrics and textiles on the second floor. This natal habitat shaped my earliest developmental years.

The rural parts of eastern Pennsylvania still a fascinating place to me, lodged in another time and era.

Narratives and people shape us as much as the places the nurture them, as I wrote a bit about here. Not just the family and the immediate surroundings but the people who preceded them, and the people before them, and the people before them, too. The Pennsylvania Dutch came after the Quakers who came after the Lenape and the Susquehannock, but they contributed shaping the region as it still is today, especially east of the Susquehanna River but also extending presently as far west as Missouri and Wisconsin.

The British fought the French and the Indians in the middle of the state, later the Yankees fought the Confederates at Gettysburg. The concentric circles of influence of country-creation and legal society also radiate from hub of Philadelphia.

Anyway, there’s the Pennsylvania I know and identify with and there’s also the me who this time and place shaped, who came from somewhere and proceeded to go places ending up here, writing this essay on paper from a sandwich shop in southeast Brooklyn.

Which, if you’re curious, seems to be an Italian-run sandwich shop in between the larger Chinese and Russian neighborhoods in southeast Brooklyn with dozens if not a hundred sandwiches named after mostly Italian or Italian-adjacent movie characters. Their menu alone is an entertaining read, a study on character interpretation through Italian-American sandwich creation and sandwich ingredients (the owners appear to be Greek). Some are named after non-Italian characters, like “the Zohan,’ which when it appeared on their TV-screen montage along with its ingredients and Adam Sandler character, sparked a conversation among the mostly white, regular labor-work attire-wearing men seemingly on a lunch break which I barely overheard while writing this on pen and paper:

[inaudible] That’s Zohan [. . .] the Jewish one [inaudible] Tax. On. Beef!

I don’t know. Maybe I misheard. I’m not sure. But there’s definitely more humor to be unveiled with the Zohan-Zohran connection. I googled “Zohan” to get a clue to why he’d have a sandwich here (he stars besides John Turturro, confirming my suspicion) and the first thing Google suggested to be on multiple computers was Zohran Mamdani.

In the Chinese owned laundromat, where my clothes were spinning while I was eating, the Chinese woman working the counter did not speak any English and changed the card dispensing machine menu from English to Spanish as she was showing me how to use it, indicating maybe a hierarchy of languages she understood? I looked around and only saw Chinese people and Muslim women inside the ‘mat but there were many Spanish speakers in this neighborhood, too.1

In many parts of New York there are demographically dominated neighborhoods and fault lines. There’s vestiges of the past, like this sandwich shop. Many of the Chinese-owned things also seem antiquated around here. I wonder how long and what factors cause a street or a neighborhood to change and how the change starts—like the Sudanese men selling cheap knockoffs on Canal Street at the fringe of Chinatown, or before that, the demographic shifts away from blue collar Europeans to Koreans in Fort Lee, NJ or from Cubans to pan-Hispanics in Union City, NJ. Or here, in southeast Brooklyn, how long the strongholds of Chinese and Russian in the neighborhoods can maintain a presence until something shifts? The Italians and Greeks of Brooklyn and Queens are still there, sometimes owning things like this sandwich shop or that real estate or small or mid-sized business, as the Jews and the Chinese seem to have done so well on doing, among other behind the scenes of things, that ever-shifting presence of change shifting and pushing these demographic groups to either evolve, move, or run-in-place, especially in a city like New York where migrants tend to land and settle for a generation or two.

The city is not all mixed-race babies and globalist elites, even though that is a part of it. Not a melting pot but mixed salad characterized by streets and neighborhoods and niches like the small corrugated steel tunnels sparrows inhabit in various scaffolding, or, more accurately, like neighborhoods that thrive when ingredients are put together and they complement each other well and are palatable that way, like how the Georgians and Turks move in next to the Russians in Brooklyn, or similarly how the Astoria of Greek immigrants evolved towards Turkish and Balkan and pan-Muslim demographic, and a Tibetan culture center filling the remote space between there and the more Flushing, a full-blown Chinatown 2.0, micro-geography imitating the layout of the macro in their microcosms. Along with some more experimental salads, like when Orthodox Jewish communities border on the edgy hip Bushwick area or the Afro-Carribean neighborhoods, or the little Thai-towns, little Bangladeshes, little Indias and whatever other little pockets are out there.

All mirroring the considerable amount of salad places that have popped up all over the place.

The lens I observe with is the lens I’ve built by selecting the things I read and invest my time in.

When I write this blog and newsletter a theme I revisit is imagination and nationhood, connecting the old worlds to the new, across seas and within the interior, and what makes nation into identity and what unpacks or uncouples them when people set foot on new soils, disengage from the past and steep themselves into novelty and modernity and postmodernity, and post-post-modernity and anything newly imagined or futuristic after that.

Nations and imaginations animate a lot of what I write about. So do migrations and itinerant identities. Diasporic communities are interesting and important to understand and not always obvious, and likewise with nationalities and nation-states. Often now more in the light of conflict resolution.

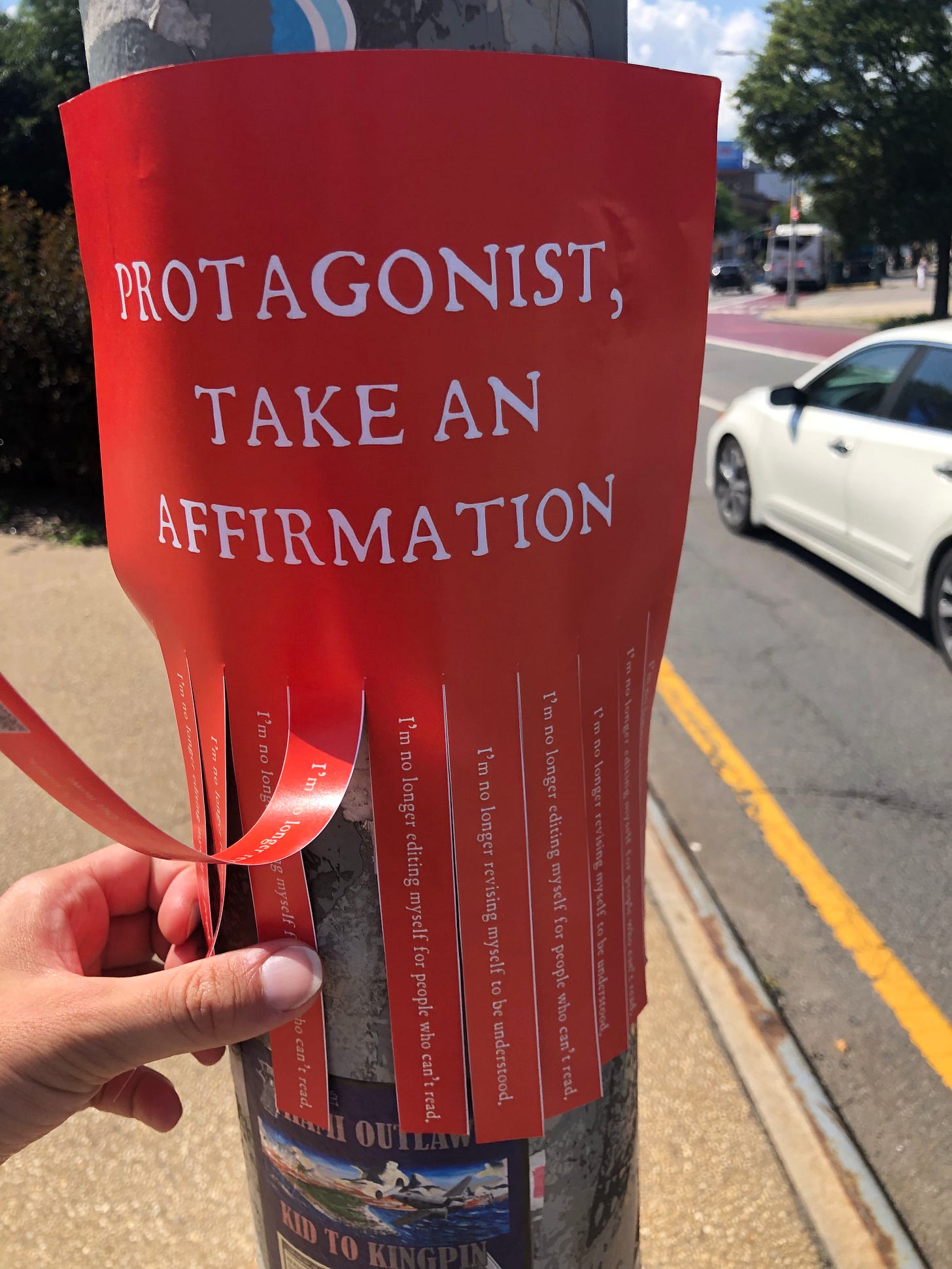

I’m also knee-deep in the skills of teaching, moderating and managing classrooms, interested in the art of doing so with diverse international classes as easily and effectively as possible. I smiled at this idiosyncratic “PROTAGONIST, TAKE AN AFFIRMATION” flyer on a pole which had two strips to rip off: “I’m no longer revising myself to be understood” and “I’m no longer editing myself for people who can’t read,” because both of these skills are essential and integral to my job, and to writing! Does that make me less protagonistic?

It’s central to how I teach people to use language and learn culture.

It motivates how I write and what I read. Does that make me less of a protagonist? An antagonist, maybe? Okay, fine. I like pushing against the grain.

For example: while teaching in between writing this on a yellow-papered legal pad and typing it up I used

’s “Against Photography” essay and the question “what do you think our age will be remembered for?” as a warm-up and conversation starter for a class, and a student brought up that “nothing’s taboo now” with a disapproving scowl. Aside from correcting her pronunciation (ta-BOO, not TAE-boo) and clarifying the meaning of “our age” (it’s not your age, but the era), neither which changed her answer, this launched a surprisingly broad and deep conversation.I pushed back: there’s plenty that’s taboo, like the things I know I can’t bring up in the classroom; in many contexts and settings a lot is still taboo. I suggested maybe she meant that nothing’s taboo online, which she retorted that it’s all popular culture, and I pushed back on the cultural variations across the country, and we settled on something else to allow some other students to speak.

I basically said what I will say on here: that taboos are shifting around across political and social lines and boundaries, and that we’re trying to find a way forward.2

Anyway, it was a class discussion I thought was supposed to be light and fun and oriented towards technology not politics, but like Elon Musk himself, the two realms are becoming less separable, so we ended up talking about a lot more.

Technology is often at the root of many social and political things, or at least it is amplifying them. I finished the class by sharing a list of images of obsolete/semi-obsolete technologies and asking them to consider which ones we should use more.

Immigration is important and worth investing more time in understanding even as the ailing-Biden(less) left dropped the ball on legislating, or at least on making many people feel comfortable about their legislation. So, we are at a point of cruel spectacle as the ostentatious “solution” to the immigration conundrum—which is far from a solution.

There’s no clear-cut obvious answer to it wholesale, there are many facets and micro-realities to it at various scales, different for varying classes and varying demographics, for varying visa types and extensions, for criminal record-holders and non-renewing overstayers, and many other numbers of things.

Also:

Nation-states are valuable ideas worth understanding better, both as nation—or people, and state—or governance. Nation-state is difficult to achieve but a worthwhile pursuit. Nation-state is underappreciated yet imperfect, opportunity-giving and flawed, underrated in its power over providing identity and stability of a people—and perhaps its greatest enemy today is the current media ecosystem we are inhabiting that tribalized more than unifies, and you are inhabiting this ecosystem now reading by this.

So.

Expect to read more book reviews/reflections while I focus and lean more into themes of nation identity and imagined orders, two things I had in mind when I titled my other Substack blog and newsletter “Secular World Order.”

And John’s Deli, apparently, is a whole thing, a half-century old institution. I merely got a little lost in my neighborhood and had no idea where to go to eat but I’m glad I stumbled upon it.

Thanks for reading,

ARW

Really this is evidence mostly of my cluelessness about where to go to do things and just picking whatever’s close or looks interesting. I’ve moved almost every month this year, and several times last year.

I had many examples in my mind, and have more now, like how it’s taboo to talk about certain wars in certain ways with certain people and in certain settings, which is one of the biggest things I am conscious of in classes with international mixes of students.