I started writing about the animation of Hayao Miyazaki following my previous posts defining science fiction versus fantasy through the work of Philip K. Dick and autoxenophilia, or over-identifying with “the other.” Instead of going too in-depth, this is one skims the surface of several Miyazaki themes.

Miyazaki’s oeuvre is rich not just in color and movement and animated detail, but in themes and historical context and personal story. All his work is essentially Japanese and of a postwar Japan milieu—giving it hints of Western-ness. Hayao Miyazaki was born in 1941 in the Empire of Japan and his father served in the Imperial Japanese Army as an airplane mechanic. Miyazaki’s themes typically revolve around unrestrained nature vs. industrial capitalism, shady adult adaptations vs. childhood coming-of-age, girl heroines and boy heroes navigating a world of ethically ambiguous adults, a re-creation of a restorative Japanese-style Shinto-inspired pantheism, learning to welcome and accept strangers and strangeness, and achieving peace amidst violent struggles or war.

These all seems pacifist and not very American or masculine. To a degree, they are not. Yet I think there’s a lot in this cocktail that reveals the postwar past and present world history that indicates where we are at right now, globally and specifically, with Americans flying a turbulent airplane uncertain of how to land it surrounded by fighter jets and filled with loud, siloed passengers debating American masculinity each strapped into their own fragmented worlds and struggling to communicate, all while their pilot and co-pilots and air traffic controllers—competent and professional—are struggling to fly and land the damn thing (and communicate, underfunded and overworked) while trying not to crash the plane let alone lose an engine.

At least that’s what I see at the heart of many exchanges on this publishing platform.

And understanding the postwar art of Miyazaki can reveal some light and clarity for all passengers, pilots and air traffic controllers.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Spirits and Mechs

In Miyazaki’s approach to wind, from Nausicaä to The Wind Rises, there’s a clue to interpreting Don Quixote’s windmills. One can see the windmills as technological “others” who harness the power of the wind, and Don Quixote as the common man whose plight is to become a hero. There’s wind, giants, and one aspiring hero interpreting them who is misinterpreted as a confused man.

It’s not just wind, but wind and giants that Miyazaki and Cervantes invoke. The windmill is a giant. Giants in Miyazaki are more subtle but present as they are so often under Japan’s rising suns, a land riddled by tsunamis and kaiju, from Godzilla to Akira, Evangelion to Attack on Titan.

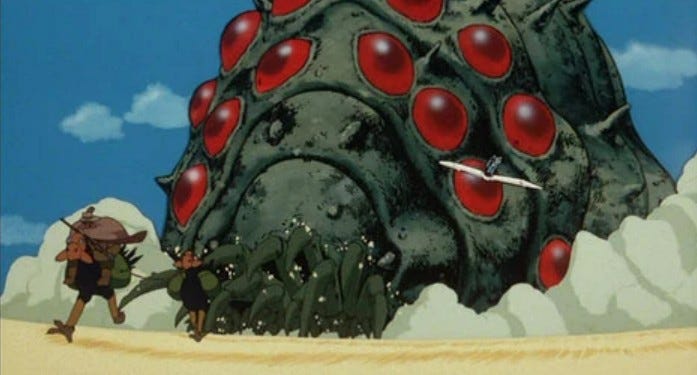

Nausicaä’s giant sentient insects (Ohmu), Kiki’s giant final set-piece airship, Mononoke’s forest-spirit-turned-nightwalker and giant boar and giant wolf god (Okkoto and Moro), Spirited Away’s gluttonous No-Face and smelly stink-spirit and oversized baby, Howl’s moving castle, and Ponyo’s entire spirit-infused land-eating sea—they are all monstrous manifestations both of nature and of man’s technological mastery. Often the spiritual giants are countered by man-made giants, in the form of giant airships, mass-manufactured guns or stranger mechanical amalgamations. In Mononoke the man-made giant is Iron Town itself. And the man-made giants are countered back by other spiritual giants. The point I want to make is that the theme of small and big, humble and huge, David and Goliath, as a trope of Japanese pre and postwar art—which has universal appeal as a greater archetype—lives through Miyazaki’s art, and it’s also a timeless anecdotal archetype represented as a feature of Spain’s cultural story in Cervantes’s Don Quixote.

The windmills that Don Quixote confronts are inert and inanimate, much unlike Miyazaki’s world of animated spirits. They stand motionless, receptive and animated by nothing more than the wind. Quixote challenges the towering objects, and this reveals more about him and his culture than it does about windmills. Quixote is the spirit, the windmill the mech.

Giants

The giants of man and the giants of the spirit are pitted against one another, not unlike they are time and again in many mechs vs. kaiju stories.

There’s an early form of this in Don Quixote, according to Spanish philosopher Oretga y Gasset1, writing before the world wars rattled the world.

The flour mills of Criptana rise and gesticulate above the horizon in the bloodshot sunset. These mills have a meaning: their “sense” as giants. It is true that Don Quixote is out of his senses but the problem is not solved by declaring Don Quixote insane. What is abnormal in him has been and will continue to be normal in humanity.

Don Quixote battles imagined giants, but he imagines them from something materially and physically real and he imagines them as psychologically real. Quixote has an imagined vision, a concept, of entity embodied by the windmill. He senses a challenge and reacts with heroic intention to triumph.

Granted that these giants are not giants, but what about the others? I mean, what about giants in general? Where did man get his giants? Because they never existed nor do they exist in reality. Whatever it may have been, the occasion on which man first thought up giants does not differ essentially from the scene in Cervantes’ work. There would always be something which was not a giant, but which tended to become one if regarded from its idealistic side.

Evangelion had giants, too. Its creator, Hideaki Anno, calls them Angels. Evangelion starts far from the comfort-food-package of Miyazaki’s digestible stories but stands as something like a polar opposite at the other side of an animated equilibrium. Evangelion’s giants are giant aliens from another planet whose wrath terrorizes the earthlings of Tokyo-3 and beyond. In Evangelion’s hyperbolic dystopia, Shinji is psychologically crippled by his overbearing father who forces him to pilot giant robot mechs that nearly sap Shinji of his lifeforce almost killing him several times over—his only alternative is letting everyone down by permitting total global annihilation at the hands of giant alien monsters.

Shinji, a boy reluctantly and without agency inheriting his plight to become Don Quixote, interprets his own giants ambiguously (are they his overbearing father or the alien “angel” kaiju?) and he reveals why Ortega y Gasset asks, “where did man get his giants? Because they never existed nor do they exist in reality. . . . There would always be something which was not a giant, but which tended to become one if regarded from its idealistic side.”2 Don Quixote’s windmills materially stand like giants towering above him but only become something to him when he interprets them through culture. This is Ortega y Gasset’s meditation.

I digress—let’s leave Hideaki Anno’s world behind.

Miyazaki is more subtle. In Nausicaä there are windmills, but they’re part of the scenery. They indicate utility and environmental harmony with the wind. They are still giants in a land of giant sentient insects. The windmills are giants designed and built to supply human settlements on the desert planet. They fade to the background while the movie’s heroes try to defend the giant insects, the Ohmu, against invading highly technologized humans who crash their giant spaceships nearby.

From the eyes of young heroes, often girls, Miyazaki imagines young, naïve human souls fighting giants. He empowers women in leadership roles, setting precedents for Japanese animation, but he also chooses girls as protagonist heroines because they are more naïvely optimistic. He often contrasts them with slightly more practical and darkly jaded young men or boys, who often develop a caring sort of love for the girls over the course of their mutual heroic journeys.

Winds of Change

Miyazaki’s postwar art is invested in Japan, but it’s integrated with a postwar American paradigm. Since the Meiji era, Japan began competing with the West—mostly Europe in the age of exploration and discovery. Imperial Japan’s ambition across Asia were a strategy to compete against industrializing and colonizing global geopolitical rivals in Europe and the UK who were building vast trade networks and far-ranging territorial outposts.

Ashitaka has to go west in the beginning of Princess Mononoke. In a Manichean way, he’s infected by evil and must fight for the good. He embarks westward, not unlike a lone hero in an American western. The journey west is not just an arbitrary pattern but built into the promise of the sunset. Like the steppe people moved west from Central Asia into Europe, like the Europeans went west to the New World, like Americans Manifested their Destiny, going west is often coded with a powerful heroic-mythic source code. (I make the case for a universal logic to this here). Even the Japanese pushed westward into Manchuria and Indonesia.

Seeping into facets of Miyazaki’s stories are the strong myths perpetuated by the increasingly powerful (now war-victorious) Western (and westward) paradigm.

From the west, postwar (and prewar) feminisms from both America and Europe influenced and enabled Miyazaki’s strong female characters, too: girls coming-of-age and challenging the norms in their own heroine and shadier anti-heroine roles. The ruthless industrial-capitalist Lady Eboshi who heads Iron Town and employs lepers and ex-brothel ladies to build guns and power her forge in a premodern Japanese forest, surrounded by a moat, enemy samurai clans, and very angry nature spirits. Her nemesis, San, the “princess,” is semi-feral and a half-human stranger to her world (not unlike Spirited Away’s Chihiro, who becomes Sen).

There’s a ton of western tropes in Princess Mononoke, informed by Miyazaki’s early stories/movies like Shuha’s Journey and Nausicaä, tropes that make his worlds a little more westernized and digestible to “the west.” Princess Mononoke is a fantasy tale grounded in western tropes, populated with dynamic heroes battling a variety of giants.

Wind, symbolically, is a sign of change. It’s a mysterious force of destruction and creation. It’s a symbol of currents and unmanageable force. Bob Dylan riddled in 1962 that the answer, my friend, was blowing in the wind. I’ve had several dreams of gale force winds at crucial pivot points in my life. The winds of hurricanes have changed American municipalities forever, Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans being one among many, and every year wind has the power to alter history and blow wildfires and change cultural currents without compromise.

Like giants, wind is both a real and symbolic force. We heroically face winds of change as we interpret them, like Don Quixote and his windmills, through culture. Miyazaki’s heroes and heroines glide with the winds, synchronizing with the times and places they inhabit and, like Japan itself after the great loss of its great imperial march, have to find an impossible and unlikely way to appease hungry and powerful giants nameable and unnamable, perceptible and imperceptible.

Airplanes

Let’s not lose the airplane metaphor, either. Perhaps the most common theme in all Miyazaki’s work is flight. Whether it’s birds, airplanes, gliders, novelty flying devices, brooms, dragons, paper-creatures, or whatever, flight is a restorative lift and gift possessed only through specialized material or spiritual qualities, work or status (spiritual often higher in status than based humans and their technology) (Ponyo is experimental in its prioritizing water over wind). In these flying mediums, the meanings of winds and giants meet. The changing currents of cultures intersect as the hero faces the shadow antagonist of the giant, however the hero interprets that giant.

Miyazaki is telling powerful postwar stories. The atomic bombs that fell on Nagasaki and Hiroshima fell from the sky, dropped by American pilots like many smaller bombs before them.

Bombed-out cities mark some of Miyazaki’s earliest childhood memories. The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki’s last and most personal movie, begins with the boy losing his mother to a fiery, bombed-to-destruction Japanese town. He goes on to meet a heron who leads him to a giant cylindrical tower which he enters then falls through a portal to another plane or spirit dimension. In this tower, protected by forest and birds, he moves through a series of ordeals (led by strong independent women) that lead him to encounter the death of his mother.

The shape of Miyazaki’s art reflects the shape of his life, like Don Quixote—a creation of Cervantes, who created a national myth for Spain—the animator is caught in the act of interpreting giants like windmills in the context of his nation at a time and place, except he’s processing something much more objectively and potentially fatal (imperial retraction after the end of the war) and historically contextual (a new postwar paradigm) to our present moment.

In the art of Miyazaki the audience witnesses both spiritual and material-technological giants competing for significance in the stories, but the more magical souls of the pilots or river-spirits or forest-spirits or broom-riding witches triumph in heart and spirit, ultimately changing both themselves and the people around them for the better, shedding light in new hopes and ways to go on.

When I see Miyazaki’s imitation in AI art this is what I see: human soul and spirit triumphing over machine and mechanical destiny. Or at least a desire and a hope that this artificial image can triumph.

That’s a noble start. But for us humans, pawns to the mighty powerful companies that control our data and material-technological destinies, the way to go on heroically against these giants is by going deeper to confronting reality, and this is a lot harder than typing well-written prompts.

That’s all for this one. May your battles with giants be integrally imagined.

ARW

This essay was a follow up to my previous essay about Philip K. Dick and the genres of sci-fi and fantasy, which you can read here.

Philip K. Dick, sci-fi, and fantasy lives

We live in one of Philip K. Dick’s imagined worlds: face-reading surveillance technology, video calls and screen ubiquity, ads beamed back at us, personalized surveillance-based targeting. Spaceships to the stratosphere filled with millionaire women, an anomalous orange American President, while “everything computers” control our lives.

From Meditations on Quixote, “Windmills” (1916). Translated from Spanish by Evelyn Rugg and Deigo Marín, W. W. Norton & Company, 1961.

From footnote 22, Meditations on Quixote